Alice, the Red Queen and ERoEI

Faster! Faster!

In Lewis Carroll’s famous story Through the Looking-Glass the protagonist, Alice, meets the Red Queen. Suddenly they start running.

Alice never could quite make out, in thinking it over afterwards, how it was that they began: all she remembers is, that they were running hand in hand, and the Queen went so fast that it was all she could do to keep up with her: and still the Queen kept crying ‘Faster! Faster!’

Alice and the Queen run faster and faster until,

. . . just as Alice was getting quite exhausted, they stopped, and she found herself sitting on the ground, breathless and giddy.

The Queen propped her up against a tree, and said kindly, ‘You may rest a little now.’

Alice looked round her in great surprise. ‘Why, I do believe we’ve been under this tree the whole time! Everything’s just as it was!’

‘Of course it is,’ said the Queen, ‘what would you have it?’

‘Well, in OUR country,’ said Alice, still panting a little, ‘you’d generally get to somewhere else—if you ran very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.’

‘A slow sort of country!’ said the Queen. ‘Now, HERE, you see, it takes all the running YOU can do, to keep in the same place.

Energy Returned on Energy Invested (ERoEI)

The Alice and Red Queen image of needing to run faster and faster to stay in the same place is a fine metaphor for the fossil fuel basis of our current lifestyles. In the early days of the oil industry not much energy was needed to find new sources and to replace what had been used. All that they had to do in those days was “stick a straw in the ground” and oil flowed. The picture below shows a gusher from an oil well in near Spindletop in south-east Texas sometime around the year 1900. The oil reservoir was close to the surface and had sufficient internal pressure to drive the oil as shown.

However, as the low-hanging fruit is plucked, an increasing fraction of the available energy has to be spent on finding and developing replacement sources. New oil sources are often at locations that are remote and that impose very difficult working conditions. The cost of finding and developing these sources is high. For example, an offshore platform in deep water can cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

The oil industry has to run faster and faster to stay in the same place.

Net Energy

The phrase, “It takes money to make money" is commonly used in the financial world. The same concept applies to energy.

It takes energy to find and utilize energy.

In order to understand the economics of the oil business, it is necessary to distinguish between Gross Energy and Net Energy. The crude oil that flows out of a well contains ‘gross energy’. It is the total amount of energy that the oil can provide when burned. However, before that oil can be supplied to a customer it has to be transported to a refinery and turned into usable products such as gasoline, aviation fuel and feedstock for petrochemical plants. All of these activities consume energy. The energy in the produces provided to the customers is ‘net energy’.

Net Energy = (Gross Energy - Energy Expended)

Another way of looking at the same concept is to consider the term ‘Energy Returned on Energy Invested’ or ERoEI. It can be defined as follows.

ERoEI = Gross Energy / Energy Expended

Let’s say that the crude oil that flows out of a well contains say 100 units of energy (Btus or kilojoules are commonly used units of measurement). Let’s further say that 10 units of energy are consumed in finding and developing the oil well in the first place, and then transporting and refining the crude. Then,

Gross Energy = 100 units, Energy Expended = 10 units and Net Energy = 90 units.

The Energy Returned on Energy Invested, ERoEI = 100/10 = 10

With regard to crude oil, we have exploited the easy-to-find and easy-to-develop resources first. We have picked the low-hanging fruit. Therefore, oil companies are forced to spend an ever-increasing amount of energy simply finding and extracting new sources of energy to replace what has been used.

It is thought that, in the early days of the oil industry ERoEI values were as high as 99, i.e., it took just 1 unit of energy to find and develop 100 units of gross energy. Over the years, as new sources of oil have become increasingly difficult to find and develop, ERoEI has fallen into the 10 - 20 range.

From a mathematical point of view, if ERoEI falls below 1 then there is no point in continuing the work because more energy is being spent on getting the oil than that oil eventually delivers to the market place. In practice, many observers suggest that, if the ERoEI value falls below 5 then there is little incentive to develop that source of oil.

One reason for this conservatism is that there are many factors that go into finding and developing new sources of oil that are not normally considered in the development of the ERoEI value. For example, government subsidies will skew any analysis. It is also difficult to define the boundary conditions and to determine which activities to include in the calculation.

Representative ERoEI Values

The concept of gross and net energy can be applied to any energy source. Shown below are representative ERoEI values for different sources of energy. Actual values will vary considerably depending on the specific circumstances.

- Hydro 100

- Oil (conventional onshore) 20

- Wind 18

- Oil imports 12

- Natural gas 10

- Solar 5

- Shale oil 5

- Bitumen tar sands 3

- Ethanol from corn <1 to 5

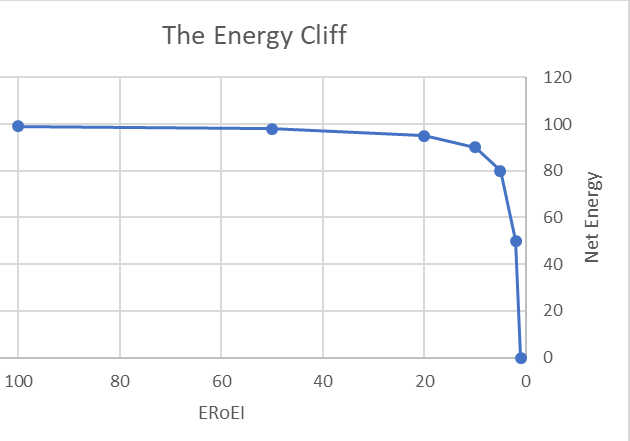

The Energy Cliff

The following chart shows the relationship between Net Energy and ERoEI. It shows that when ERoEI reaches a value of about 5 the return on energy invested drops precipitately. We fall off the energy cliff.

As ERoEI declines, so does Net Energy. When ERoEI remains above 10 plenty of Net Energy is available. However, at that point the amount of energy available for use starts to decline steeply. When ERoEI is less than 5 very little Net Energy is available. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the Energy Cliff. (This is why the phrase ‘Peak Oil’ does not mean that we run out of oil. It means that we run out of affordable oil, i.e., the point where it is no longer economic to develop new sources of oil even though they are present in the ground. Peak Oil occurs at the point where we start to fall of the energy cliff.)

This way of thinking challenges the standard economic statement that, “If prices go up then supply will increase correspondingly”. No amount of money will justify the development of new resources if the resource itself is required for the development process, and if that resource is in irreversible decline.

Productivity Slowdown

The concept that we have less free energy for use in business activities can help explain some of the standard economic dilemmas. For example, in the year 2015 the economist Robert Samuelson wrote an editorial entitled, “Productivity mysteriously goes bust” for the Washington Post. He starts the piece by saying,

What’s surprising about the disappointing slowdown in productivity is that, by all outward signs, it ought to be booming. What’s especially baffling is that, superficially, outside forces seem to favor faster productivity growth.

The outside forces that he alludes to include the internet, activist investors and globalization.

All of these forces should have resulted in improved productivity, but they didn’t. He concludes by saying,

The productivity bust is a big story. It’s also a bit of a mystery.

The reason for the decline in productivity that Samuelson talked about — a decline that has continued since he wrote the editorial — may be due to declining Energy Returned on Energy Invested. Energy is the ultimate resource for all of society’s activities, so when energy goes into economic decline so do many other things.

Copyright © Sutton Technical Books. All Rights Reserved. 2021.