Safety Moment #79: The Process Safety Consultant

This Safety Moment is one in a series to do with the process safety profession.

Many of the publications that we offer are to do with the topic of Process Safety Management (PSM), or with related topics such as the offshore Safety and Environmental Management System (SEMS) and Safety Cases. Therefore, it is useful to spend a few moments examining the fundamentals of process safety. It is important to know what process safety management is, and — just as important — to understand what it is not.

Process Safety Management (PSM) is not new; indeed it has always been an integral part of management in the process and energy industries. (If it has to have a formal start date then the follow-up to the explosion at the Flixborough plant in England in the year 1974 is probably a good choice — which is why the picture at the top of this page is from that disaster.)

Companies have always had systems in place for carrying out activities such as the writing of procedures, planning for emergencies, training of operators and the investigation of incidents. But it was in the late 1980s and early 1990s that PSM programs became more formalized and regulated. In the United States the key regulation was 29 CFR 1910.119, Process Safety Management of Highly Hazardous Chemicals, from OSHA (the Occupational Safety & Health Administration). It became effective in the year 1992. This regulation served as a model for the PSM programs used in many other nations and for internal programs developed by many large energy and process companies.

Offshore, the American Petroleum Institute (API) Recommended Practice 75 and related documents (such as RP 14J) formed the basis for similar management programs offshore.

Inevitably, when a program such as Process Safety Management (PSM) becomes so widespread and has been in use for so long, its meaning can become altered or diluted. So, it is useful occasionally to step back and consider just what PSM is — and, by implication, to consider what it is not. Probably the best way of doing so is to examine each of its component words: ‘Process’, ‘Safety’ and ‘Management’. But first, it makes sense to consider the historical background to the development of PSM in order to provide context for the discussion.

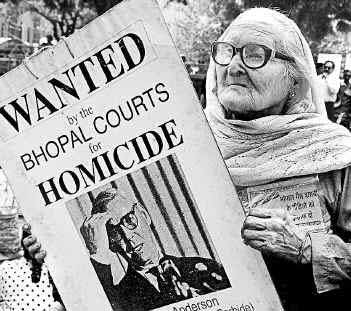

In the late 1980s various chemical plants in Texas experienced severe explosions and fires. And in the year 1984 the town of Bhopal in India witnessed the world's worst catastrophe involving the chemical industry. The official death toll for that event was 3,787 — and many more people suffered severe and disabling injuries. The overall impact of these events was to create a sense that “something must be done”.

In the United States, Congress reacted to this concern by incorporating process safety management requirements into the Amendments to the Clean Air Act legislation. The legislation required that both OSHA (the Occupational Safety and Health Administration) and the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) issue regulations to do with process safety. The upshot was OSHA’s Process Safety Management program (29 CFR 1910.119) and the EPA’s Risk Management Program (RMP). They focus on worker and public safety respectively.

The OSHA standard, which was published in the year 1992, has become something of a “go-by” for many other PSM programs, including those prepared by companies for their own internal use.

It is important to understand that neither OSHA nor the EPA actually wrote their respective regulations — that was done for them pre-emptively. In the late 1980s executives from some of the largest chemical companies recognized that the introduction of a process safety regulation in the United States was inevitable as a result of the incidents just discussed. So they took the initiative. Working with the Organization of Resource Counselors, these companies developed a standard that really would help improve safety — not just add another layer of bureaucracy or impose arbitrary rules. And the key to their approach was to make sure that the new PSM standard would be both performance-based and non-prescriptive. This was important because there is such a wide variety of processes and technologies; development of detailed standards for all of them would have been very time consuming and inefficient.

Published in 1988, their report was entitled “Recommendations for Process Hazards Management of Substances with Catastrophic Potential.” The document served not only as the basis for the regulations from OSHA and the EPA, but also for offshore standards such as API RP 75, 750 and SEMS.

It is noteworthy that these early standards worked. Not only did they help improve safety, they also helped companies improve their overall operations, including production and system availability.

Over the years process safety programs have been modified and expanded. But the original concept of having a non-prescriptive/performance-based standard has held up well. So it makes sense to take a step back and to look at the basics of process safety management developed a generation ago. Otherwise, there is a danger of seeing only the details and of losing sight of the forest for the trees.

The Center for Chemical Process Safety (CCPS 2007b) provides guidance as to what constitutes a PSM event.

Given that the principles of process safety are also used offshore, the word “chemical” in the above definition should be understood to include flammable and explosive materials.

The final bullet point is important. Although an effective process safety program will help improve environmental and health performance, that is not its goal. The focus of PSM is on sudden, short-term events that could have catastrophic consequences.

In order to understand the basics of Process Safety Management it is useful to examine each of the three words that make up that phrase.

The first word in the phrase ‘Process Safety Management’ is Process. PSM is to do with the management of complex chemical and energy industrial processes. There are many other types of safety program, such as behavior-based safety and occupational safety, and PSM has links to these. But, fundamentally, PSM is about understanding complex process and energy facilities that generally involve the use of sophisticated technology, exotic chemicals and hard-to-understand feedback loops and multiple-contingency events. This is not easy.

There are many instances of companies having an excellent occupational safety record and then suffering from a major fire or explosion. (Examples include the Deepwater Horizon and Longford ncidents.) The management of these companies failed to understand that process safety results are achieved not by people performing their work more safely — process safety can only be achieved when everyone involved understands the very nature of the processes that they are designing or operating, and then figuring out how things can go awry, and what to do about it.

To re-iterate: this is not easy.

Safety is the second word in the term ‘Process Safety Management’.

The purpose of a PSM program is to identify and then manage process hazards that could result in serious injury or death. If the program also generates improvements in the environmental and health programs — as it probably will — then such improvements are an incidental benefit. They are not what PSM is about.

Many PSM professionals maintain that their work also helps companies become more productive and profitable. It is difficult to unequivocally prove this point of view. But, it is argued that, if a company has a good safety management program then it therefore has a good management program. This will result in improvements to all aspects of the operation.

The third word in the term ‘Process Safety Management’ is Management.

A fundamental premise of Process Safety Management is that safety — and operations in general — can be managed, i.e., that, in principle, all systems, both technical and human, can be understood rationally, and can be controlled. To put it another way, there is no such thing as luck, nor are there Black Swans (an idea that is, however, challenged somewhat in Safety Moment #11: Black Swans and Bow Ties).

For this reason PSM professionals tend not to use the word “accident” because of its suggestion that things “just happen”. Any “accident”, it is argued, could have been prevented had better management systems been in in place.

Each company, industry, regulator and standards-setting society has its own way of organizing a PSM program. But many of them are based on the venerable fourteen elements published by OSHA in the year 1992. They are:

Since the publication of this list in the early 1990s other organizations, such as the CCPS (Center for Chemical Process Safety) have developed improved versions, as shown below. But the striking reality is that the list first prepared by the committee working with Organization of Resource Counselors has held up so well.

Copyright © Ian Sutton. 2018. All Rights Reserved.

This Safety Moment is one in a series to do with the process safety profession.

If you fly over the offshore platform of the future in a helicopter and look down you will see just two living beings: an operator and a dog. The operator’s job is to feed the dog; the dog’s job is to make sure that the operator doesn’t touch anything.

2020-06-03

In the post SEMS and Risk in 2020 (SEMS if the offshore equivalent of process safety management as applied to U.S. deepwater operations — mostly the Gulf of Mexico), Mick Will, says,

2020-05-27

I would like to take a break from talking about this virus this week. (Wouldn’t we all?) Instead, let’s take another long-range look as to where the process industries may be going, and how safety management programs may have to adapt.

2020-05-20

In this post I would like to consider how those of us who work in industrial and process safety can help the community at large? The subject came to mind when I was discussing the eventual return of people to church services with a colleague. Our Episcopal diocese has organized a four-phase program for the re-opening of the churches (we are currently in Phase One).

In any performance-based program such as process safety, the work is never finished — there is always room for improvement.

In practice, most of the developments in techniques for improving safety analysis are improvements of existing programs or techniques. For example, the hazards analysis technique LOPA (Layers of Protection Analysis) has seen widespread application in recent years. Yet it is basically a development of the well-established Fault Tree and Event Tree techniques.

The Deepwater Horizon/Macondo catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico (GoM) in the year 2010 demonstrated the need for new safety management regulations. The draft regulations went through various iterations, and the name of the responsible government agency changed twice. In the end, the SEMS (Safety and Environmental Management System) regulation became a requirement for offshore oil and gas operations in the United States.

The Chemical Safety Board (CSB) conducts investigations into serious incidents that occur in the chemical and process industries. The following quotation is taken from the web site of the United States Chemical Safety Board.

The CSB is an independent federal agency charged with investigating industrial chemical accidents. Headquartered in Washington, DC, the agency's board members are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

© 2017-2025 Ian Sutton Technical Books & Modules | All rights reserved

Proudly built in Richmond, VA by Garza Web Design